About this Blog:

"Bring On The Lumière!" -- is an interdisciplinary performance at the intersection between dance, theater, cinema, and light installation, inspired by the Lumière Brothers, the French founders of cinema.

Conceived by choreographer Catherine Galasso, "Bring On The Lumière!" premiered at ODC Theater (San Francisco) in November 2011, followed by New York performances at Joyce SoHo in January 2012. Generously supported by the San Francisco Foundation, ODC Theater Artist-in-Residence Program, Headlands Center for the Arts, Atlantic Center for the Arts, CHIME Mentorship program, the Andrew Mellon Foundation, and individual donations.About "Bring On The Lumière!"

Attend a Performance

Catherine's WebsiteFUNDING CREDITS

-

Recent Posts

Categories

Archives

Meta

Monthly Archives: January 2013

New video! Bring On The Lumière! “Behind the Scenes” with director and cast

Bring On The Lumière! “Behind the Scenes” with director and cast

Director Catherine Galasso and performers Christine Bonansea and Marina Fukushima talk about the process and ideas behind Bring On The Lumière! during a post-show talkback at ODC Theater in San Francisco.

All music in this video by composer Michael Galasso.

All footage by Mark McBeth, November 2011

© Catherine Galasso 2013

Return to the cave: writings by Selby Schwartz about Bring On The Lumière!

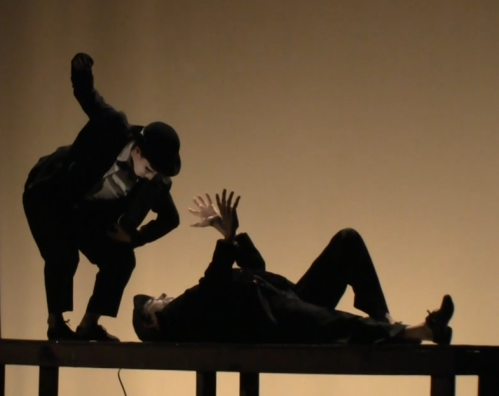

Marina Fukushima and Christine Bonansea in Bring On The Lumiere!

ODC Theater 2011, video still by Mark McBeth

Below is an excerpt from Selby Schwartz’ piece about Bring on the Lumière! which will be published in the forthcoming Oxford Handbook of Screendance Studies (edited by Douglas Rosenberg.) Selby approached me about writing this piece, and we invited her to observe rehearsals for Lumière. In the process she became integral to the development of the work as an outside eye and sounding board. In general it was a great pleasure to have her around – especially when Christine, Marina and I could make her laugh!

Dancers Leaving the Factory: Catherine Galasso’s Bring on the Lumière

by Dr. Selby Wynn Schwartz

(excerpt)

Catherine Galasso’s Bring on the Lumière! (2011) re-animates Auguste and Louis Lumière (who died in 1954 and 1948, respectively), in an elegiac, affectionate, and sometimes uncanny tribute to the origins of film history. In bringing the Lumière brothers back into life through dance, Galasso asks us to reflect on the relationship between live bodies and the ghostly preservation of those bodies as images on film. For the Lumière brothers, cinema was the dazzling progeny of photography, and its essential quality was documenting the ephemera of a moving world through technologies of light. Bodies were a special category of ephemera, and early cinema was particularly attracted to physical activity—dancing, rowing, playing pétanque. On the surface, this was because images could finally represent live motion; underneath, though, there was a dark hinting at the impermanent material reality of bodies themselves, as they moved through time towards death.

In early cinema’s fascination with mechanical innovation and the rush to document and preserve, it identified with narratives of light: it was miraculously luminous, a repeatable and reproducible beam projected from the past, a bright remainder. It offered an alluring possibility of casting those precious, evanescent bodies in light and celluloid, where it would keep their images after they had disappeared. However, cinema is also born of a long history of shadows. Its roots in the tradition of shadow-theater and shadowgraphy tell a different story, one that relied absolutely on the live presence of physically skilled performers and body-to-body transmission. In one way, Bring on the Lumière! is about bringing the Lumière brothers back to life as only dance can—by giving them wondrous new bodies to inhabit. In a deeper way, it is also about restoring a pre-history of early cinema, a narrative that has been obscured by the excitement of industrial light and magic. This is a dance of Edison bulbs and carnival tricks, and it tells the history of shadows made by real bodies.

The governing metaphor of cinema is Plato’s description of the cave of fantastical shadows that, projected on a wall, create the flickering illusion of reality.(1) As film theorist Andé Gaudreault points out, from this model we understand that “the film image is a simulacrum of a simulacrum,” because of the double artifice of the projection (From Plato 150). The philosopher Jean-Claude Dumoncel clarifies the logic behind this claim: “the shadows on the rear wall of the cavern are not shadows of a tree or a bull but rather shadows of statuettes: they are copies of copies” (qtd. in Gaudreault, From Plato 150). If cinema follows this Platonic model, though, it has a strangely distant relation to bodies, and especially to performing bodies. It is the technology here that is essential—the statuettes, the firelight, even the chains that bind the audience to a fixed perspective—but there is no place for live performers.

Usually, the tension in the uneasy interdependence between dance and film is attributed to the fact that dance is a live, sweaty, precariously present medium—inadequately rendered by film or video as flat, fixed, repeatable, and coldly distant from kinesthetic experience. (2) But the early history of cinema, as well as cinema’s ongoing self-identification with the Platonic story of the cave, imply that the issue lies not just with dimensionality and temporality: it is a conflict between a medium at two removes from bodily experience and a medium absolutely centered in the body. How can dance bring a quality of lived bodily experience back to cinema, when there is clearly an anxiety about the loss that occurs when three-dimensional live dance is filmed in two technologically-framed dimensions? In order to decipher new intermedia performances like Catherine Galasso’s Bring on the Lumière! that integrate live dance and recorded film, we have to return to the cave, and to the pre-history of cinema in Europe—in short, to the realms of shadow theater. […]

Notes:

(1) This narrative exerts an almost irresistible attraction; even Susan Sontag, opening her book On Photography with a section titled “In Plato’s Cave,” clearly intends to discuss how photography follows this Platonic model, but is quickly drawn into a statement about how movies “light up walls, flicker, and go out” (3). Her first two examples in this ontology of photography are Godard’s film Les Carbiniers and Chris Marker’s film Si j’avais quatre dromadaires (3, 5).

(2) As André Lepecki writes, “It is one of dance studies’ major premises to define dance as that which continuously plunges into pastness—even as the dance presents itself to visibility… But there is also an inscription of the dance onto the mnemonic mechanisms of technology, either through photography, film, [etc.]… Between one kind of memory and the other, the question of the presences of the dancing body becomes a matter of delicate excavation” (4). Matthew Reason points out that contemporary high-definition digital recording has not even resolved the issue of representing dance ‘faithfully’ in photography, much less in video or film: “the difficulty of representing movement in still photographs remains a relevant issue in the age of video recording” (45).

Works Cited:

- Gaudreault, André. From Plato to Lumière: Narration and Monstration in Literature and Cinema. Trans. Timothy Barnard. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009.

- Lepecki, André. “Introduction: Presence and Body in Dance and Performance Theory.” Of the Presence of the Body. Ed. André Lepecki. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2004. 1-9.

- Reason, Matthew. “Still Moving: The Revelation or Representation of Dance in Still Photography.” Dance Research Journal, 35/36 (Winter, 2003 -Summer, 2004): 43-67.

- Sontag, Susan. On Photography. New York: Anchor Books, 1977.

About Selby

Dr. Selby Wynn Schwartz

Selby Wynn Schwartz received her PhD in Comparative Literature from UC Berkeley, and is currently a lecturer in Columbia University’s interdisciplinary pilot program in Writing and Gender Studies. Her articles have appeared in Women and Performance, PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art, Dance Research Journal, Critical Dance/Ballet-Dance Magazine, In Dance, and in the forthcoming issue of Conversations Across the Field of Dance Studies: Visual Culture and the Performing Arts. In 2010, she received the Society of Dance History Scholars’ Lippincott Award for the Best English-language Article in Dance Studies. In addition to working with Alonzo King LINES Ballet, Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo, and Monique Jenkinson, she has taught at UC Berkeley, the LEAP program, and the BFA program at Dominican University of California. She is presently finishing a book on drag and dance.

Posted in Creation